The Science of Spelling

What is the Science of Spelling?

The Science of Spelling is a systematic approach that involves understanding the relationship between sounds and written symbols.

It utilises the large body of Science of Reading research to implement evidence-based best practices and strategies to teach and practise spelling. Learning to spell is a key ingredient to becoming a good reader and is far more intricate than just memorising words.

Each lesson has a main objective taken from the relevant year’s content descriptors. Committing each word to memory would be an enormous and daunting task for any learner. Instead, The Science of Spelling teaches children to recognise spelling patterns and highlights notable exceptions. Words are taught in context and linked to other words with similar patterns in order to fully explore their meanings.

Why is Spelling Important?

It’s easy to think that in a world full of emojis, abbreviations and spell-checkers, spelling might not be as important as it once was. But the truth is, spelling matters more than ever, not just for correctness, but for communication, confidence and connection.

Daffern and Fleet (2021) state that, “In an age of fast-paced digital modes of communication such as texting, emailing, and messaging through social media platforms, it seems more important than ever to be able to efficiently spell words in a range of contexts.”

Written language is a form of communication, and errors in spelling can lead to misunderstandings or a loss of meaning. While the basic idea may still be conveyed, messages with frequent spelling errors often lose their authority and tone.

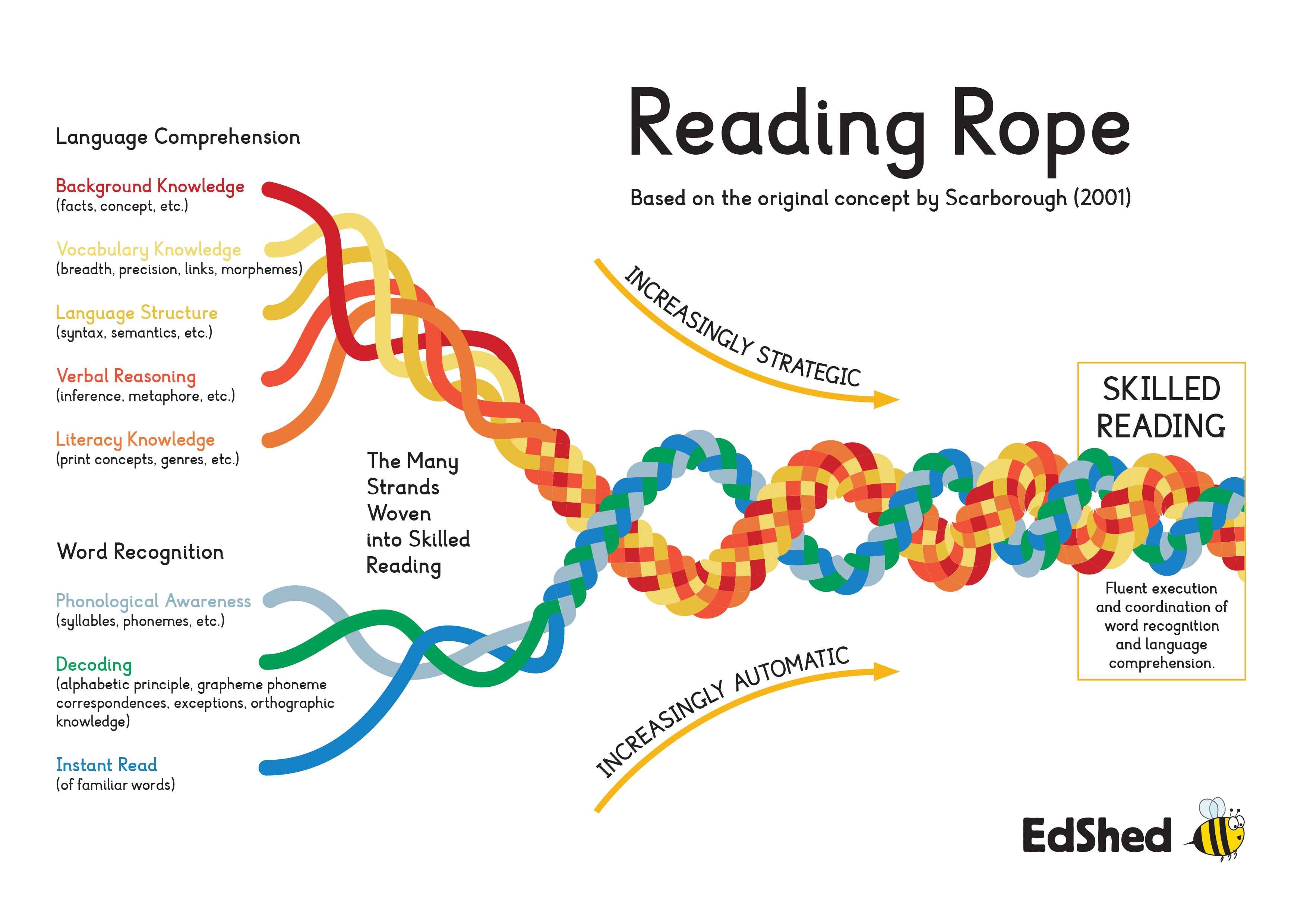

How Does Spelling Impact Reading?

Learning to spell is a key ingredient to becoming a good reader and is far more intricate than just memorising words. Catherine Snow et al. (2005) summarise the real importance of spelling for reading as follows: “Spelling and reading build and rely on the same mental representation of a word. Knowing the spelling of a word makes the representation of it sturdy and accessible for fluent reading.” Encoding (spelling) is a developmental process that impacts fluency, writing, pronunciation and vocabulary. Fluency is best developed through a combination of mastering systematic phonics, practicing high frequency words and repeated readings (Moats, 1998; LeBerge & Samuels, 1974; Rasinski, 2009).

As students begin to master phonics, it is advantageous to use those skills to practice the 300 high frequency words that make up 65% of all texts (Fry, 1999). When the relationship between spelling and reading is conveyed, students gain a better understanding of the code and demonstrate gains in reading comprehension (Moats, 2005), vocabulary (Moats, 2005), fluency (Snow et al., 2005) and spelling (Berninger, 2012).

When spelling is taught meaningfully, students become curious about words. They notice connections between words like magic and magician, or sign and signal. They realise that spelling isn’t random; it tells a story about where a word comes from, what it means, and how it relates to other words.

The case for meaningful spelling instruction

Let’s begin by stating what meaningful spelling instruction is not:

- It’s not memorising weekly lists with no discussion of why the words are spelled that way.

- It’s not copying words out ten times in different colours.

- It’s not presenting ‘exceptions words’ as mysteries to memorise.

- It’s not disconnected from reading or writing, where students never see words used meaningfully in context.

- It’s not one-size-fits-all. Students learn best when instruction matches their current understanding.

The above practice of trying to memorise the spelling of words in isolation might seem harmless, traditional, even, but research shows it’s one of the least effective ways to help children become confident, capable spellers.

As Dr Misty Adoniou (2016) puts it, “We simply don’t have the brain capacity to learns tens of thousands of strings of letters and recall them every time we write a word.” When children simply copy or chant words over and over, they may remember them for a test on Friday, but by Monday they’ve been forgotten and, more often than not, those same words are misspelled during writing activities. That’s because the children are storing the words only in short-term memory, without developing a deeper understanding of how or why those words are spelled that way.

A deeper look at what the research says

Spelling is about far more than accuracy; it’s about understanding how our language works. When children learn to spell, they’re uncovering the patterns, structures and histories of words. This knowledge strengthens their reading, writing and vocabulary, giving them the confidence to communicate ideas clearly and creatively.

Dr Louisa Moats (2005) explains that spelling instruction does far more than teach correct letter sequences; it reinforces reading proficiency and vocabulary growth. Learning to spell draws on knowledge about sounds, print patterns and meaning, all of which strengthen students’ ability to recognise and recall words when reading.

Moats also challenges the belief that English spelling is irregular and unpredictable. She shows that it follows consistent linguistic principles once students are explicitly taught to look for them, including phoneme–grapheme relationships, morphological patterns and word origins. Regular, systematic instruction in these areas helps students become more confident writers and fluent readers.

Building on these ideas, Dr Misty Adoniou (2016) reminds us that English spelling isn’t random or full of exceptions; it’s a highly organised system built on meaning. When students explore why words are spelled the way they are, through roots, prefixes, suffixes and word origins, they begin to see spelling as logical and fascinating rather than frustrating.

“Good spellers are good readers, and both skills rely on knowing how words work.” — Dr Misty Adoniou (2016)

Sue Scibetta Hegland highlights the importance of teaching morphology (the meaningful parts within words) and etymology (word origins) from an early age. By going ‘beneath the surface of words’, students discover the logic that ties words together. This approach is particularly powerful for struggling spellers, who often thrive when they’re given tools that make sense of the spelling system rather than relying on rote memory.

“English is structural, and the morphemic elements within written words provide the framework.” — Sue Scibetta Hegland (2021)

How Does Spelling Shed Use The Science of Spelling to Deliver Effective Spelling Lessons?

At Spelling Shed, our approach to teaching spelling is grounded in research, particularly the Science of Spelling and the Science of Reading. Effective spelling instruction isn’t about memorising lists; it’s about teaching students how words work. That means giving them strategies they can use, not rules to remember.

We use direct instruction, guided word study and targeted practice to help children understand the relationships between sounds, letters and meaning. Every Spelling Shed list has been carefully developed to follow a systematic progression of skills typically introduced at each Stage.

As Dr Louisa Moats (2005/2006) reminds us, “Spelling is a visible record of language processing. If we know how to look at a child’s spelling, we can tell what they understand about language.” Our lessons are designed to make that understanding explicit, helping students connect phonemes (sounds) and graphemes (letters) while exploring the meaning and structure of words.

So, what is meaningful spelling instruction?

Meaningful spelling instruction involves exploring how sounds, letters and meanings connect, discovering patterns and logic, and linking spelling with reading, writing and vocabulary. It’s making space for curiosity, asking why a word is spelled that way. It’s explicit, systematic and responsive to each learner’s needs. It empowers them to become analytical, self-reliant, and joyful users of language.

“An effective speller draws upon the entire rich linguistic tapestry of a word in order to spell it correctly. The threads of this tapestry can be identified as:

- phonology – the sounds of the word

- morphology – the meaningful parts of the word

- etymology – the history of the word, and

- orthography – the conventions of spelling that have developed over time”

— Dr Misty Adoniou (2016)

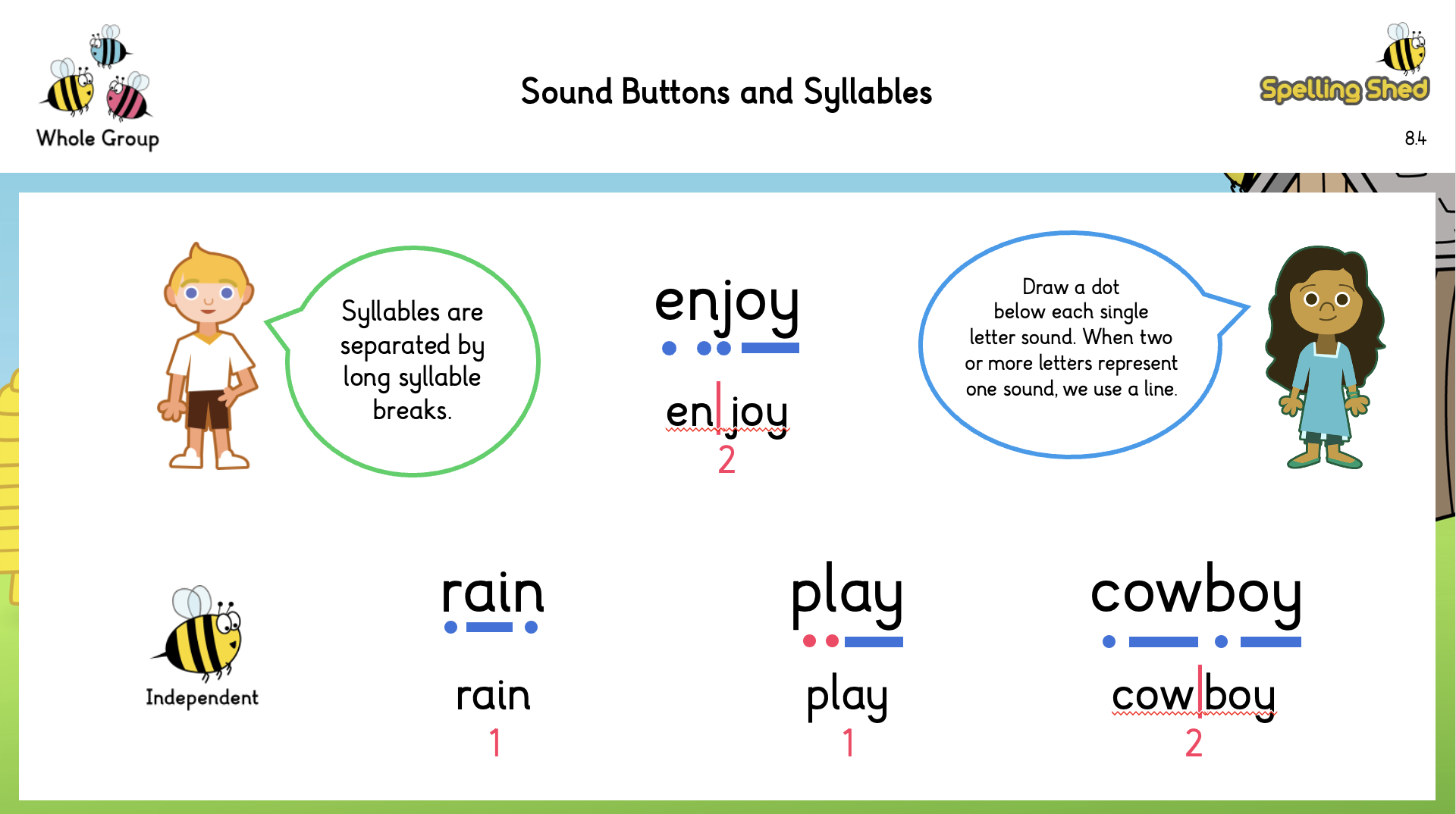

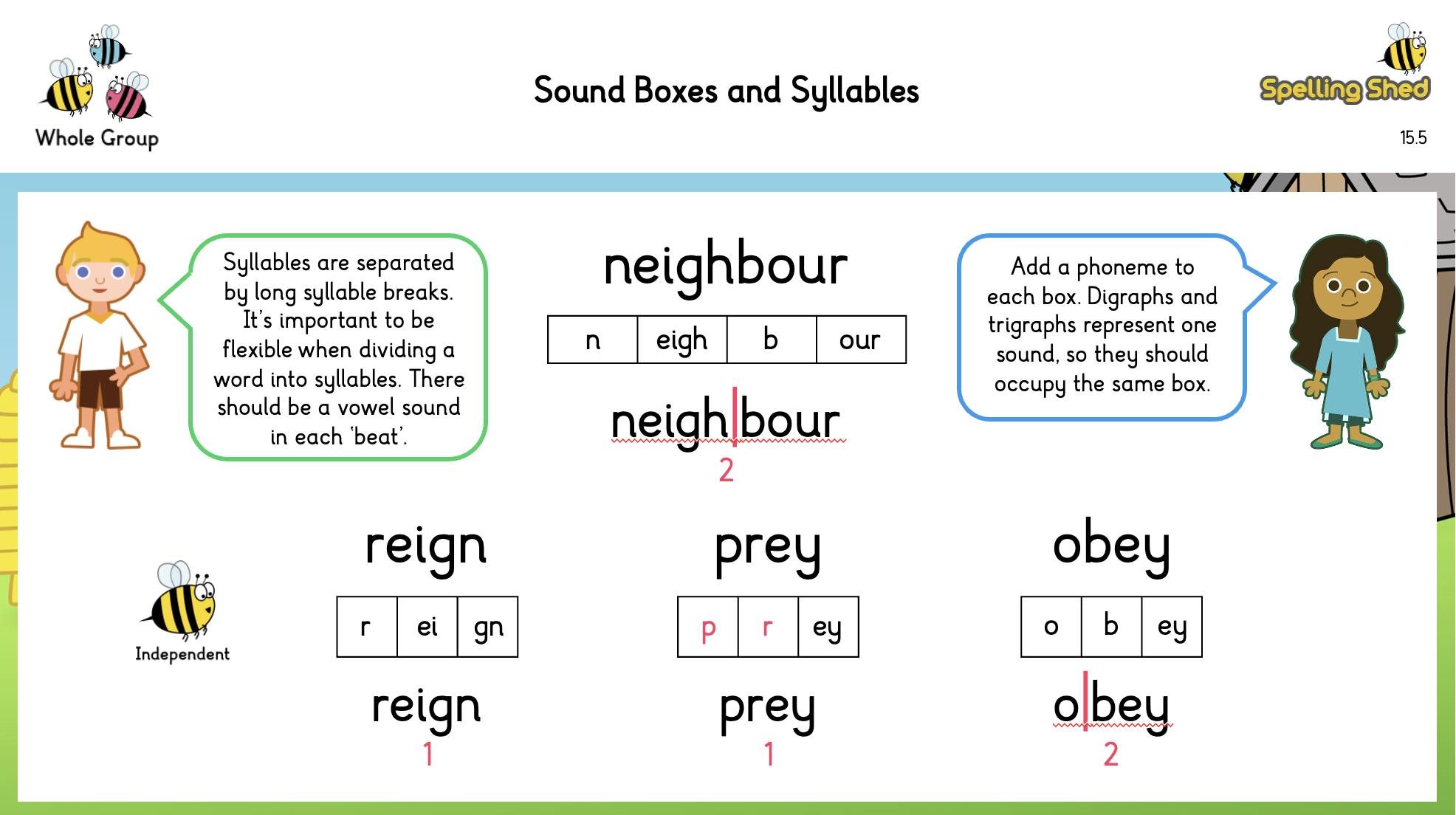

Phonological Knowledge

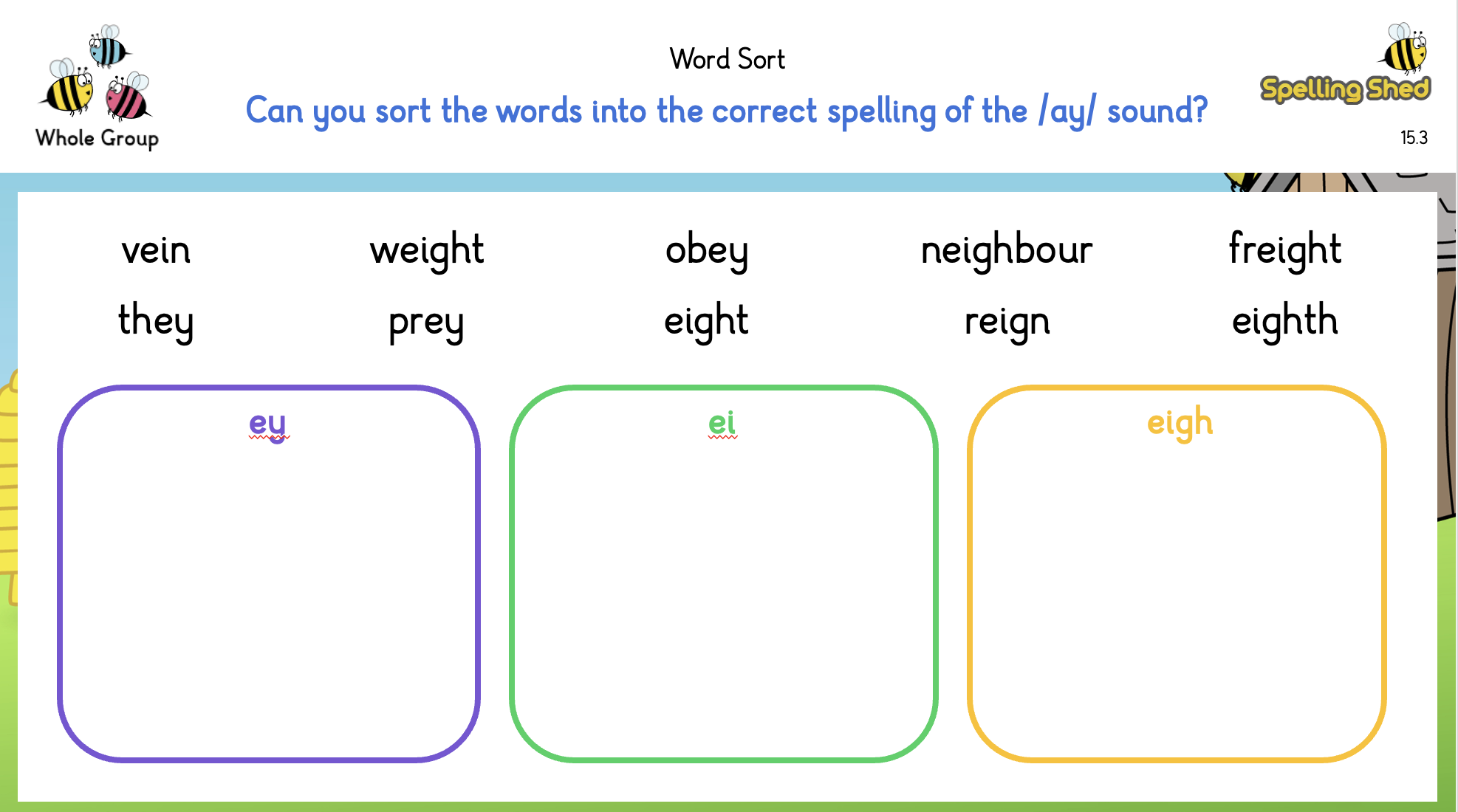

This is knowing which graphemes (letters, digraphs, trigraphs etc.) to use to represent a phoneme (sound). Using Spelling Shed, students are systematically taught the different graphemes for each phoneme. Beginning with sound buttons, then moving to sound boxes later in the scheme.

Orthographic Knowledge

“Alongside phonological knowledge, students must have orthographic knowledge, that is, understanding which letter sequences are both possible and plausible in English.” Adoniou (2024)

‘Ortho’ means ‘correct’ and ‘graph’ means ‘to do with writing’. Orthography is the study of how letters and letter patterns represent sounds in written English. Students learn that spelling is not random but follows consistent patterns that show how words are structured. By recognising these patterns and understanding their position and frequency within words, students can apply this knowledge to read and spell with confidence.

For example, in the word ‘cat’ the /k/ sound could be represented by the graphemes ‘k’, ‘c’, ‘ck’, ‘ch’, ‘cc’ and ‘que’. Learning about orthography will teach children that the /k/ sound would most likely not be spelled ‘ck’ or ‘cc’ as these digraphs never appear at the beginning of English words, and that ‘c’ or ‘k’ are a far better choice.

Morphological Knowledge

“Visual memory is dramatically better when meaning can be attached to the to-be-remembered pattern.” Bowers & Bowers (2017)

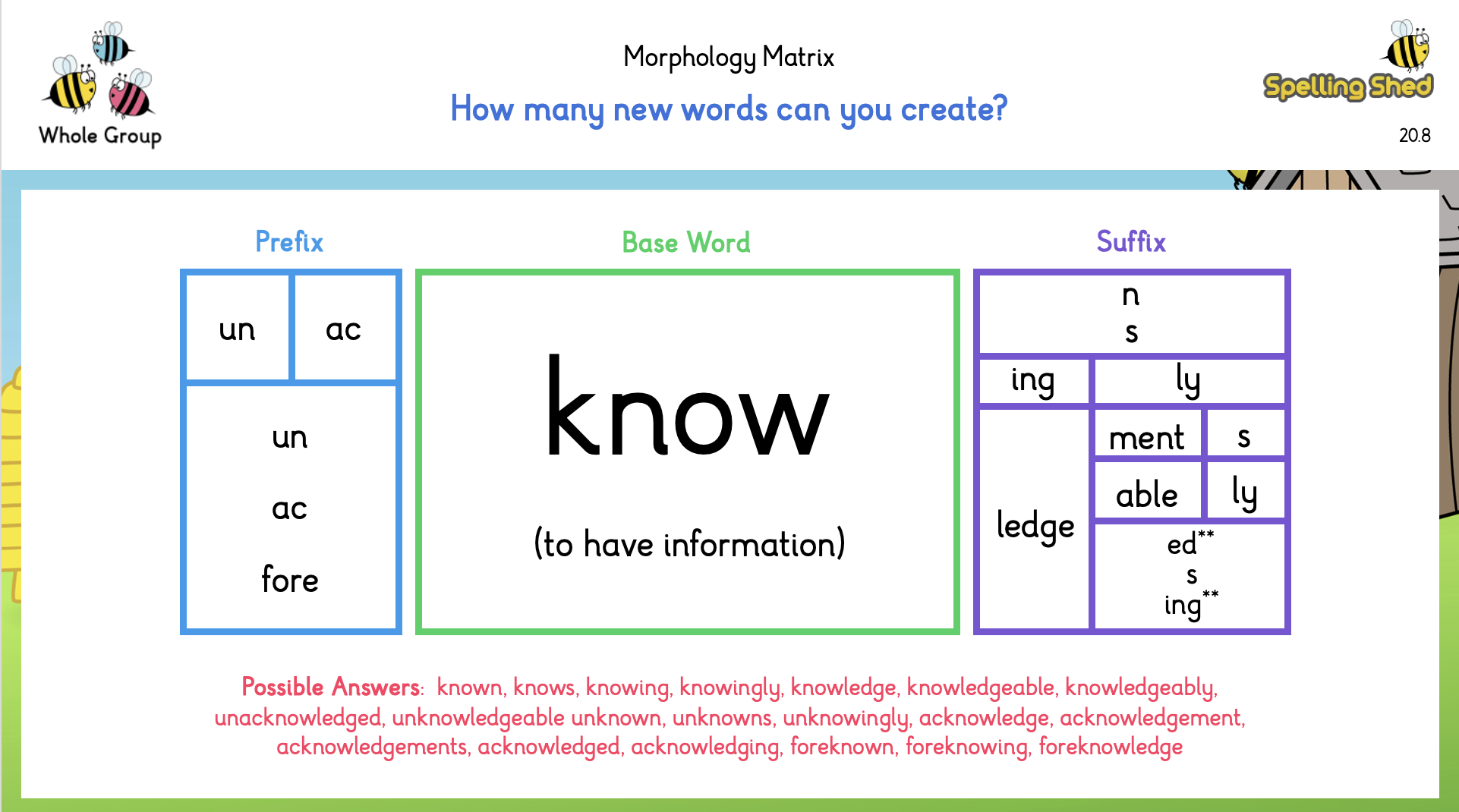

Morphology looks at how words are built and how smaller parts, called ‘morphemes’ (the smallest units of meaning), come together to form them. When students understand morphology, they can break words into meaningful parts such as prefixes, suffixes and root/base words. Recognising common prefixes and suffixes gives valuable clues about both a word’s meaning and its spelling. For example, the prefix un- often means “not”, as in unhappy, and understanding this helps students spell and make sense of related words.

Etymological Knowledge

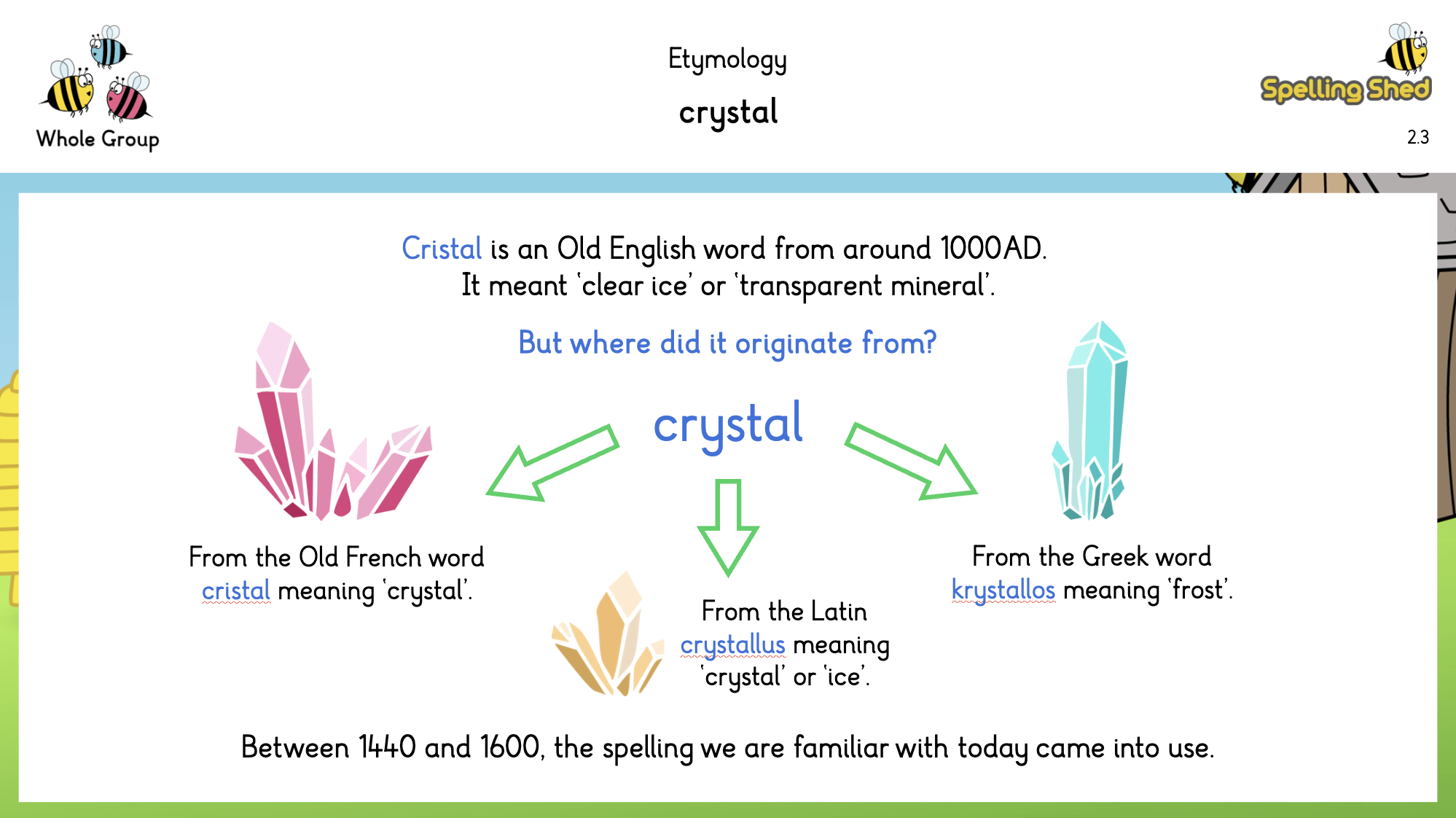

“The word etymology comes from Greek, and it means ‘the study of the reason’. Etymology is the answer to why a word is spelled like it is.” Dr Misty Adoniou (2016)

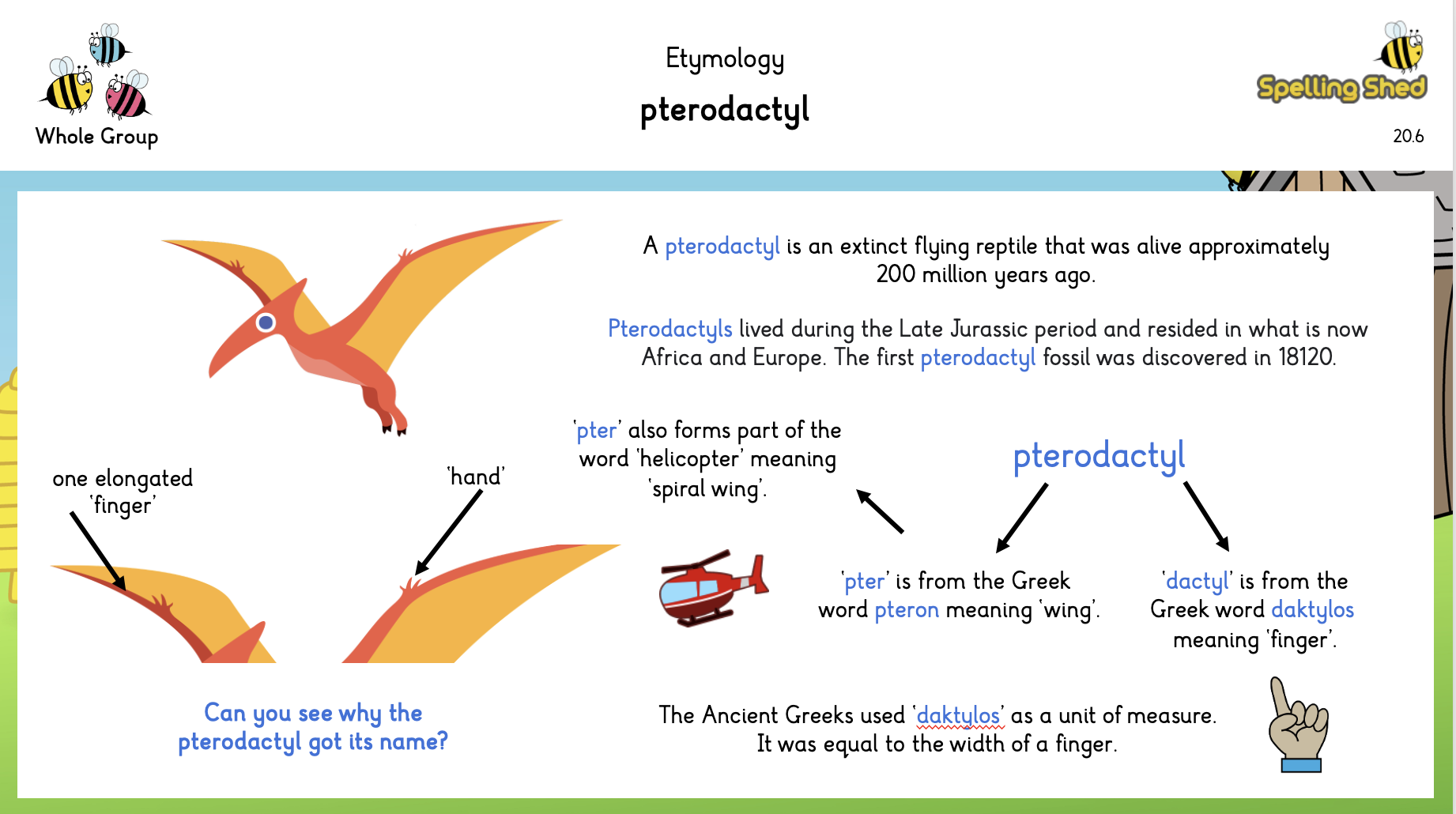

Etymology explores the origins and histories of words. Many English words come from other languages, such as Latin, Greek and French, and their spellings often reflect these origins. Knowing the source of a word often provides insight into its spelling and meaning.

In words of Greek origin, the digraph ‘ch’ often represents a /k/ sound. This is found in words such as ‘chaos’, ‘school’ and ‘stomach’. In words of French origin, the same ‘ch’ digraph can represent a /sh/ sound as in ‘chef’, chalet and ‘brochure’.

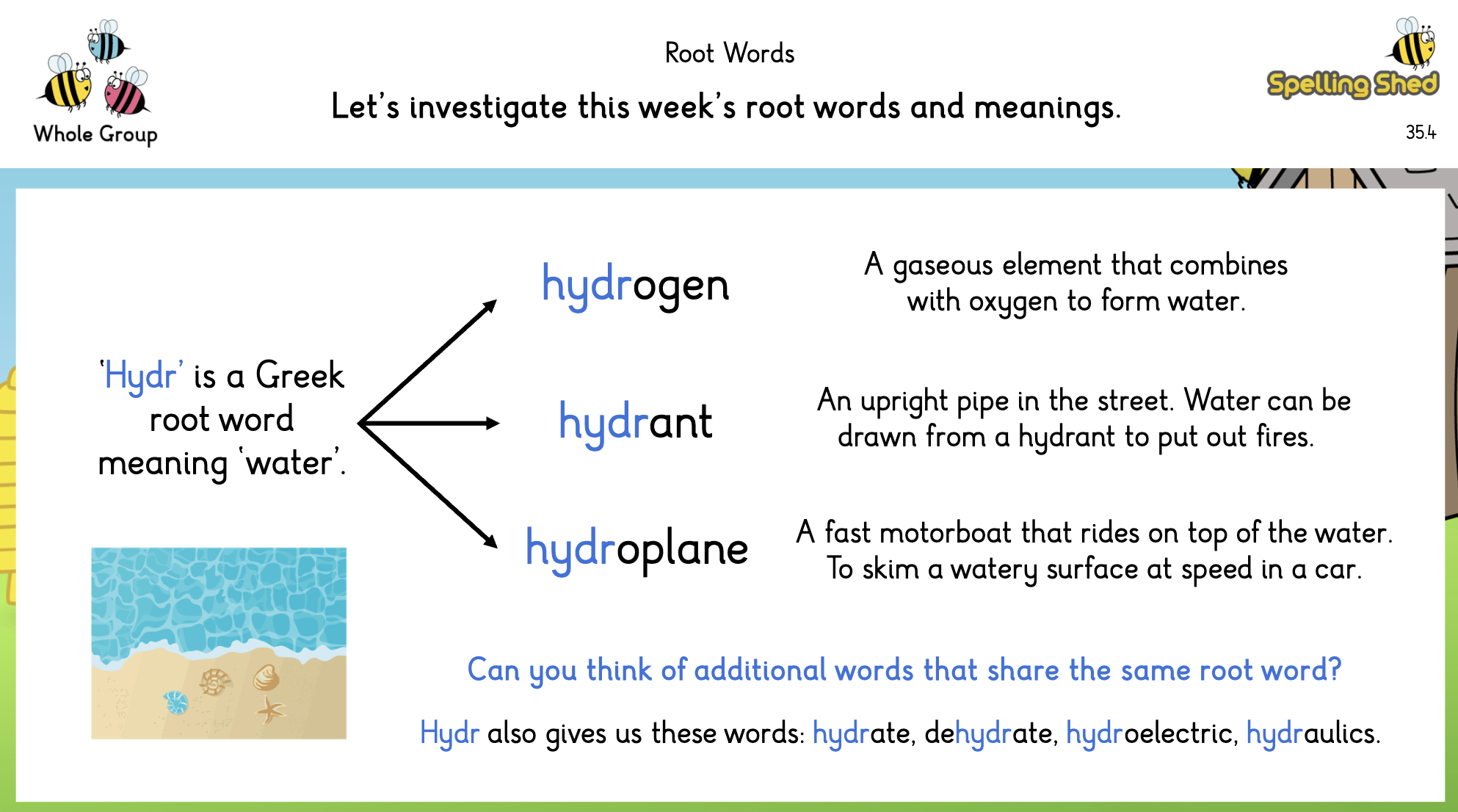

In addition, words with similar roots or bases often have similar spellings and meanings. For instance, if you know that the root word ‘hydr’ means ‘water, you can apply this knowledge and understand other words with the same root, such as ‘hydrate’, ‘hydrant’ or ‘hydrogen’.

By learning where words come from and how they are built, students begin to see meaningful connections between word families.

Understanding roots, base words, prefixes and suffixes helps them recognise patterns, making it easier to learn and remember new words. This deep knowledge of etymology not only supports accurate spelling but also strengthens vocabulary and comprehension.

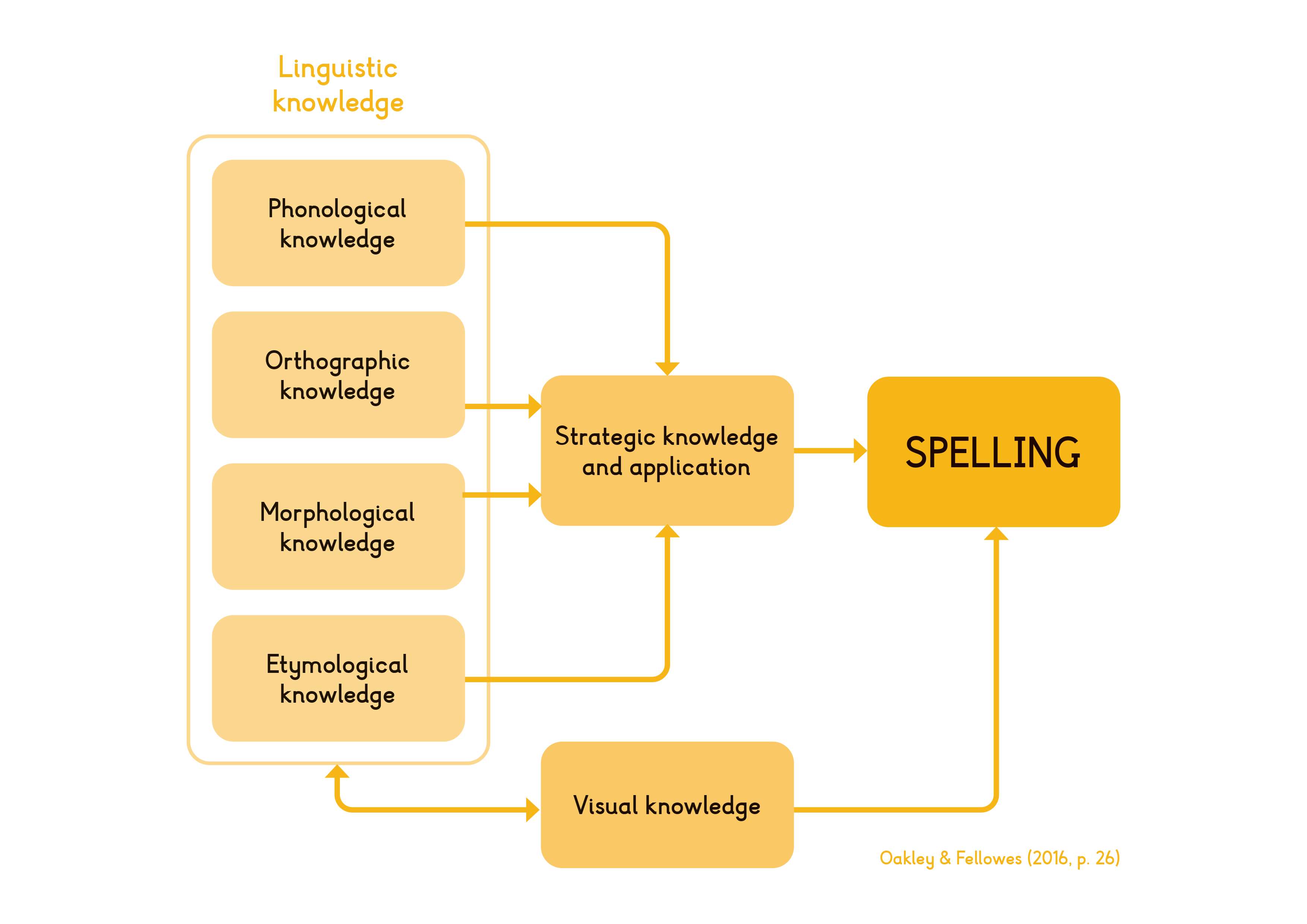

Memorised Words and Strategic Knowledge in Spelling

Effective spellers don’t just memorise words, they understand how words work. While visual memory helps us store familiar spellings, research shows that true spelling skill comes from knowing how sounds, letters and meaning connect.

“Spelling relies on multiple sources of knowledge — phonology, orthography, morphology and etymology.” (McMurray 2016; Bowers & Bowers 2017)

In other words, children learn to see spelling as a system, not a guessing game.

At Spelling Shed, we teach strategies that build this understanding step by step. Students begin with explicit phonics instruction, developing an awareness of how spoken sounds map to written letters. As they progress, we introduce morphology (the meaningful parts of words) and etymology (word origins), helping them to decode and encode with confidence.

Learning becomes increasingly strategic: children analyse patterns, explore meanings and connect word families. As Moats (2005) explains, spelling develops through “the gradual integration of information about print, speech sounds, and meaning”. Through guided and independent practice, students strengthen their word knowledge, building a mental store of words they can recall and apply effortlessly in reading and writing.

Connecting language, logic and a love of words

The Science of Spelling shows that English is not chaotic; it is a beautifully structured system that links sound, meaning and history. At Spelling Shed, we embrace this view by helping children explore how and why words work.

When students learn to see spelling as logical and meaningful, they become curious, confident and capable readers and writers. That is exactly what effective spelling instruction should achieve.

References:

- Adoniou, M. (2016). Spelling it out: How words work and how to teach them. Cambridge University Press.

- Berninger, V. W. (2012, January 23). Evidence-based, developmentally appropriate writing skills K–5: Teaching the orthographic loop of working memory to write letters so developing writers can spell words and express ideas. Presented at Handwriting in the 21st Century?: An Educational Summit, Washington, D.C.

- Bowers, J., & Bowers, P. (2017). Beyond phonics. [Book exploring the logic of English spelling including morphology, etymology, and phonology].

- Daffern, T., & Fleet, R. (2021). Investigating the efficacy of using error analysis data to inform explicit teaching of spelling. Australian Journal of Learning Difficulties.

- Ehri, L. C., & Snowling, M. J. (2004). Developmental variation in word recognition. In C. A. Stone, E. R. Silliman, B. J. Ehren, & K. Apel (Eds.), Handbook of language and literacy: Development and disorder (pp. 433–460). New York: Guilford Press.

- Fry, E. B. (1999). 1000 instant words: The most common words for teaching reading, writing, and spelling. Westminster, CA: Teacher Created Materials.

- Hegland, S. S. (2023). Developing morphological awareness: What matters for literacy. Learning About Spelling.

- LaBerge, D., & Samuels, J. (1974). Toward a theory of automatic information processing in reading. Cognitive Psychology, 6(2), 293–323.

- McMurray, S. (2016). The case for frequency sensitivity in orthographic learning. Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs.

- Moats, L. C. (1998). Teaching decoding. American Educator, Spring/Summer, 1–8.

- Moats, L. C. (2005/2006). How spelling supports reading: And why it is more regular and predictable than you may think. American Educator, Winter 2005–2006, 12–43.

- Moats, L. C., & Snow, C. E. (2005). How spelling supports reading. American Federation of Teachers, 1–13.

- Rasinski, T. V. (2009). Introduction: Fluency—the essential link from phonics to comprehension. In Essential readings on fluency (pp. 1–10). Newark, DE: International Reading Association.

- Snow, C. E., Griffin, P., & Burns, M. S. (Eds.). (2005). Knowledge to support the teaching of reading: Preparing teachers for a changing world. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass